AI Image Generation: Hidden Environmental Costs

AI image generation is more resource-intensive than it seems. Every image created consumes about the same energy as fully charging a smartphone. Multiply that by millions of users generating images daily, and the energy use becomes massive. For example, producing 1,000 images with a model like Stable Diffusion XL emits as much CO₂ as driving 4.1 miles in a gas-powered car.

Key takeaways:

- Energy Use: AI models require significant electricity, with data centers projected to consume 1,050 terawatt-hours annually by 2026 - equivalent to Japan's total electricity use.

- Water Demand: Cooling systems for AI servers consume millions of gallons of water daily, straining resources, especially in arid regions.

- Carbon Emissions: Generating 1,000 AI images can produce emissions comparable to driving several miles, with energy grids' carbon intensity playing a big role.

- Hardware Waste: AI hardware has short lifespans, contributing to growing e-waste, projected to reach 16 million tons by 2030.

The rapid growth of AI tools like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney highlights the need for energy-efficient models, renewable-powered data centers, and better recycling practices to reduce their impact on resources.

Energy Consumption in AI Image Generation

High Computational Demands

The energy required for generating AI images can vary significantly depending on the type of model used. For instance, Transformer-based models, such as Lumina, use around 4.08 × 10⁻³ kWh per image. In contrast, U-Net-based models, like LCM_SSD_1B, consume just 8.6 × 10⁻⁵ kWh per image - a stark 46-fold difference. This disparity highlights the higher computational demands of transformer architectures.

"U-Net-based models tend to consume less than Transformer-based ones, reflecting the greater computational complexity inherent to transformer architectures." – Giulia Bertazzini et al., University of Florence

A significant portion of energy consumption comes from diffusion models, which require 20–50 denoising steps for each image. These steps, executed on high-performance GPUs like the NVIDIA RTX 3090, draw substantial power. For example, the RTX 3090, operating at 350 watts, takes about 20 seconds to generate a 1024×1024 image, using approximately 1.94 watt-hours of energy.

Resolution is another energy driver. Doubling an image's dimensions can increase energy consumption by 1.3 to 4.7 times, depending on the model. User behavior compounds this issue, as creating a single final image often involves over 50 iterations. This iterative process dramatically increases energy use, especially when large generative models are employed for tasks better suited to smaller, purpose-specific models - resulting in up to 30 times more energy consumption.

Beyond individual image generation, the infrastructure supporting these processes adds another layer of energy demand.

Data Center Energy Usage

The data centers powering AI image generation are under immense energy strain. Servers and GPUs account for roughly 60% of the total electricity consumption, while cooling systems use anywhere from 7% in hyperscale facilities to over 30% in less-efficient enterprise centers. AI training clusters, with their extreme power density, consume seven to eight times more energy than standard computing workloads.

"A generative AI training cluster might consume seven or eight times more energy than a typical computing workload." – Noman Bashir, Computing and Climate Impact Fellow, MIT

Energy usage doesn’t stop at direct GPU consumption. Maintaining idle capacity for low-latency responses and accounting for Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) overhead (from cooling and power conversion) significantly increase the total energy footprint. While narrow measurements might estimate energy use at 0.10 watt-hours per prompt, a more comprehensive view - including data center overhead - reveals figures closer to 0.24 watt-hours per prompt. This broader perspective underscores the hidden energy costs behind seemingly simple AI tasks.

sbb-itb-58f115e

Carbon Emissions from AI Image Generation

Carbon Footprint of Training Models

Training AI models for image generation comes with a hefty carbon cost. For example, training OpenAI's GPT-4 reportedly consumed about 50 gigawatt-hours of energy - enough to power San Francisco for three days. In the case of 2D latent diffusion models, the training process emits carbon equivalent to driving 6.2 miles, while generating images adds emissions equal to driving 99 miles. For 3D synthesis models, the training emissions are comparable to driving 56 miles, and generating images can produce emissions equivalent to driving up to 2,079 miles.

Where the training takes place also plays a huge role in carbon emissions. For instance, Google's data center in Finland ran on 97% carbon-free energy in 2022, but facilities in Asia relied on just 4% to 18% clean energy due to a greater dependence on fossil fuels. This disparity means that the same training job could create up to 94 times more carbon emissions depending solely on the energy mix of the local grid.

"The geographic region of the data center plays a significant role in the carbon intensity for a given cloud instance, and choosing an appropriate region can have the largest operational emissions reduction impact." – Jesse Dodge et al., Research Scientists

For widely used models, the emissions from generating images can quickly outpace the initial training emissions. In fact, for some popular models, this can happen within just a few weeks due to high user demand. While the training phase creates a one-time carbon impact, the ongoing use of these models significantly adds to the overall emissions.

Emissions from Individual Image Generations

Although training happens once, every image generation adds to the cumulative carbon footprint. For example, generating 1,000 images with a model like Stable Diffusion XL produces about the same amount of CO₂ as driving 4.1 miles in a gasoline-powered car.

When scaled up, the impact becomes staggering. Ten million Stable Diffusion users consume approximately 1.92 terawatt-hours of electricity annually - similar to the total electricity use of Mauritania. Expanding this to platforms like Midjourney and DALL-E 2, with a combined 48.5 million users, raises the yearly energy consumption to about 9.29 terawatt-hours, which matches Kenya's annual electricity demand. A striking example is the app Lensa AI, which saw 12.6 million downloads in December 2022 due to its "Magic Avatars" feature, causing a sharp rise in the use of carbon-intensive diffusion models.

A critical factor in these emissions is the carbon intensity of the local power grid, which measures how much CO₂ is emitted per kilowatt-hour of electricity. Data centers, which operate 24/7, often rely on energy sources with a carbon intensity estimated to be 48% higher than the U.S. average. As AI adoption grows, projections suggest that by 2030, the industry could produce between 24 and 44 million metric tons of CO₂ emissions annually.

Water Usage for Data Center Cooling

Cooling Systems and Water Consumption

AI image generation requires a significant amount of water to cool the servers in data centers. Large facilities can use as much as 5 million gallons of water per day, which matches the daily water consumption of a town with 10,000 to 50,000 residents. To put this into a broader context, U.S. data centers collectively consumed around 66 billion liters of water in 2023.

Water usage in data centers falls into two main categories: direct and indirect consumption. Direct usage refers to the water lost on-site through evaporative cooling systems, which release vapor to manage the heat produced by servers. Indirect consumption happens at power plants that generate the electricity powering these facilities. Notably, 80% of the freshwater withdrawn for cooling towers evaporates during this process. As server hardware becomes more powerful and generates more heat, the demand for cooling - and water - only increases.

AI hardware, which has a higher power density compared to standard servers, produces even more heat, leading to greater cooling requirements. This is evident when training large AI models. For instance, training GPT-3 at Microsoft’s U.S. data centers consumed an estimated 700,000 liters of freshwater through evaporation. Similarly, training xAI's Grok 4 model required approximately 750 million liters (198 million gallons) for cooling. These figures highlight the growing environmental strain tied to AI development.

Even individual AI image generation contributes to this water demand. For example, generating a single 100-word AI prompt (often sourced from an AI prompt library) is estimated to use 519 milliliters of water, roughly the size of a standard water bottle. Other analyses suggest that 10 to 50 medium-length AI responses consume about 500 milliliters of water. When millions of users engage with AI tools daily, these seemingly small amounts add up quickly.

The scale of water usage also varies by location. In hot, arid regions like Arizona, data centers may require up to 9 liters of water per kilowatt-hour of energy used. In contrast, cooler climates that utilize outside air for cooling can cut water consumption almost entirely. However, the situation is particularly challenging in water-scarce areas. Over the past three years, more than 160 new AI data centers have been built in water-stressed U.S. regions. For example, in Loudoun County, Virginia, home to approximately 200 data centers, water usage reached 900 million gallons in 2023 - a 63% increase since 2019. These numbers underscore the resource challenges tied to AI infrastructure, particularly in areas where water is already in short supply.

Resource Depletion and Hardware Demands

Mining for Rare Earth Materials

The hardware behind AI image generation hinges on rare minerals like gallium, indium, and cobalt. While professionals use image generation prompt collections to streamline their creative workflows, the physical infrastructure supporting these tools remains resource-intensive. Extracting these materials comes with steep environmental and social costs. They're critical for building the chips, processors, memory, and storage systems that power AI infrastructure, but the process leaves a significant environmental footprint. This impact is measured using Abiotic Depletion Potential (ADPe), and nearly all of it - close to 100% - stems from hardware production rather than energy consumption. As chip technology advances, with nodes shrinking to 5nm processes, the environmental toll per square centimeter of silicon die grows. On top of that, the increasing number of graphics cards required to train AI models further intensifies the demand for raw materials.

"The rare earth minerals essential for modern chips come from mining operations that devastate ecosystems and exploit labor, often in regions far from where AI systems are ultimately deployed." - Bowdoin College

In 2021 alone, chip manufacturing generated 874 kilotons of toxic waste, adding to its environmental burden. This waste includes heavy metals like tungsten, copper, and arsenic, which often contaminate waterways near manufacturing sites.

Short Hardware Lifecycles

The environmental challenges don't stop at extraction. The short lifespan of AI hardware exacerbates the problem. GPUs in AI data centers typically last only 1–3 years due to the rapid pace of performance improvements. Enterprise-grade storage systems and GPUs, though slightly better, are often replaced every five years. This relentless push for better performance accelerates hardware turnover.

"GPUs used in AI data centers are typically retired after only one to three years, largely due to rapid performance turnover. This short lifespan contributes significantly to hardware waste." - Anton Shilov, Tom's Hardware

This quick turnover leads to "impact shifting", where energy savings during hardware use are offset by the emissions tied to manufacturing. Between 2020 and 2030, generative AI is expected to produce 1.2 to 5.0 million tons of accumulated e-waste. Adding to this, the memory size of workstation GPUs has grown at an annual rate of about 30% from 2013 to 2023, driving up the need for more raw materials.

"The environmental impact of AI cannot be reduced without reducing AI activities as well as increasing efficiency." - Clement Morand, Université Paris-Saclay

To address the rising tide of e-waste, adopting circular economy practices could make a difference. Strategies like resource recovery, remanufacturing, and designing hardware for longer lifecycles could cut AI-related e-waste by 16% to 86%. However, the industry often prioritizes performance over sustainability, leaving future generations to grapple with mounting electronic waste and infrastructure challenges. These short hardware lifecycles not only strain resources but also contribute heavily to the growing e-waste problem, as discussed further in the next section.

AI’s footprint – beyond energy consumption | Sophia Falk | IWE in 2 min

E-Waste Generation from AI Infrastructure

As hardware lifecycles grow shorter, the volume of e-waste generated by AI infrastructure is becoming a pressing concern. This issue stems from the rapid turnover of components like GPUs, CPUs, specialized accelerators (such as TPUs), storage devices, and networking hardware that power AI systems. Projections suggest that e-waste from these sources could reach a staggering 16 million tons by 2030.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that 78% of global e-waste in 2022 ended up in landfills or informal recycling sites. This discarded hardware not only pollutes the environment with hazardous substances like lead, chromium, and mercury but also contains recoverable metals - including gold, silver, and platinum - worth between $14 billion and $28 billion.

"This e-waste stream could increase, potentially reaching a total accumulation of 1.2–5.0 million tons during 2020–2030, under different future GAI development settings." – Nature Computational Science

The rapid pace of AI advancement adds to the problem. Many AI servers are replaced after just three years of use to maintain operational efficiency and processing power. Additionally, geopolitical trade restrictions on advanced semiconductors could lead to a 14% increase in AI-related e-waste, as affected regions may resort to using older, less efficient hardware to meet their computational needs.

Disposal Challenges of AI Hardware

The growing pile of e-waste also brings unique disposal challenges. AI hardware often contains sensitive data, which must be securely erased before disposal. This requirement makes the recycling process more expensive and complex.

"AI products tend to be trickier to recycle than standard electronics because the former often contain a lot of sensitive customer data." – Kees Baldé, e-waste researcher, U.N. Institute for Training and Research

Regulatory gaps further exacerbate the issue. While some U.S. states have implemented e-waste policies, there is no federal law mandating electronics recycling. International regulations also lack consistent enforcement.

Despite these obstacles, there are ways to mitigate the problem. Extending a server's lifespan by just one year can reduce total e-waste by 62%. Repurposing equipment for non-AI applications or reusing components like GPUs for art and design can cut e-waste by 42%. Adopting circular economy practices across the AI value chain has the potential to decrease e-waste by 16% to 86%. Additionally, the high concentration of valuable materials in e-waste could make recycling financially viable, turning discarded hardware into new, useful products.

Environmental Impact Comparison Table

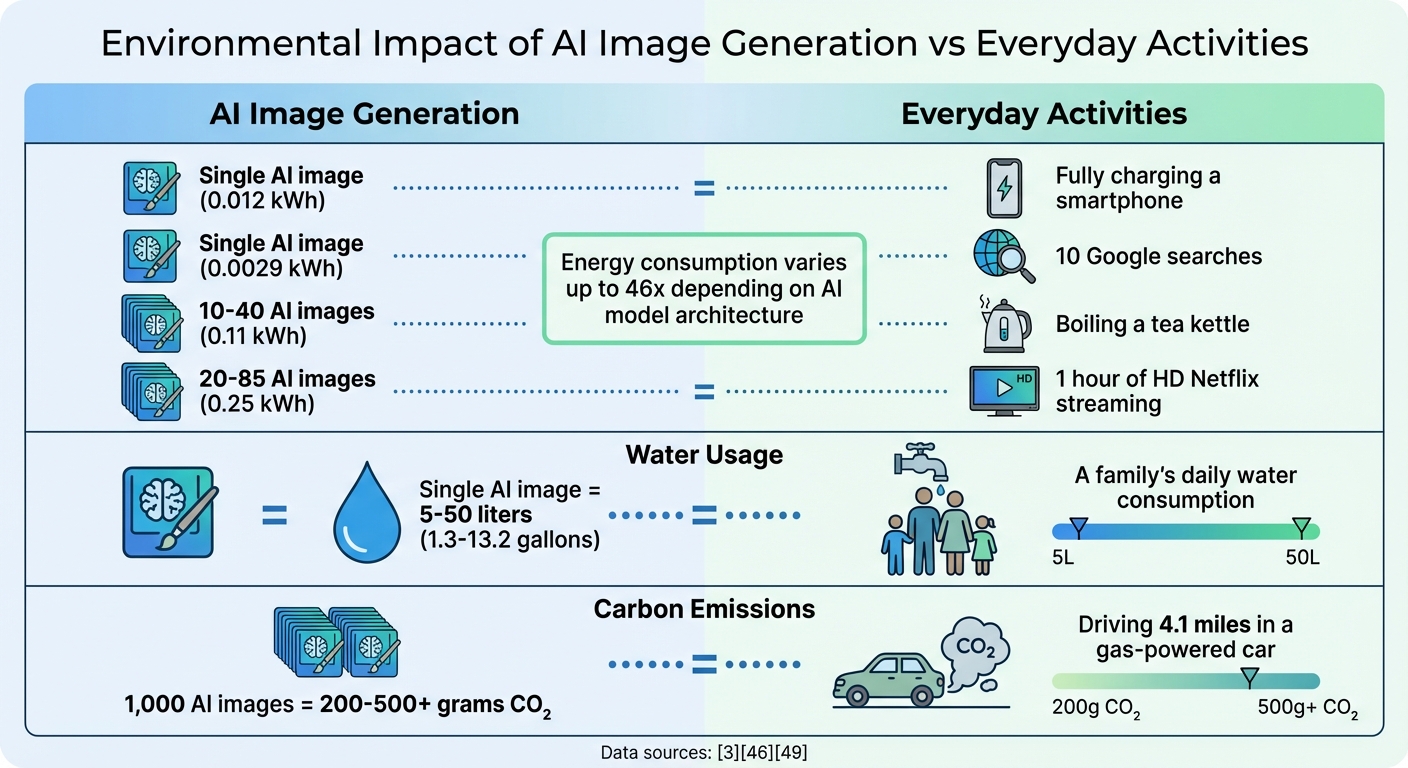

Environmental Impact of AI Image Generation vs Everyday Activities

Looking at AI image generation alongside everyday activities helps put its resource demands into perspective. The table below simplifies key metrics, making it easier to understand the environmental costs of this technology.

Table Overview

Research shows that creating a single AI-generated image uses about the same amount of energy as fully charging a smartphone - roughly 0.012 kWh. To put it another way, this is comparable to the energy needed for about 40 Google searches.

"Generating an image using a powerful AI model takes as much energy as fully charging your smartphone." – Sasha Luccioni, AI Researcher, Hugging Face

Water usage is another consideration. Cooling data centers for one AI image can consume between 5 and 50 liters (1.3–13.2 gallons) of water, which is roughly equivalent to the daily water use of an entire family. Additionally, the carbon footprint of generating 1,000 images compares to driving 4.1 miles in a gasoline-powered car.

The table below breaks down energy, water, and carbon impacts, showing how they align with familiar activities.

| Metric | AI Image Generation | Equivalent Everyday Activity | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (per image) | 0.012 kWh | Fully charging a smartphone | |

| Energy (per image) | 0.0029 kWh | Running 10 Google searches | |

| Energy (10–40 images) | 0.11 kWh | Boiling a tea kettle | |

| Energy (20–85 images) | 0.25 kWh | Watching 1 hour of HD Netflix | |

| Water (per image) | 5–50 liters (1.3–13.2 gallons) | A family's daily water consumption | |

| CO2 (1,000 images) | 200–500+ grams | Driving 4.1 miles in a gas car |

The energy consumption of AI models can vary significantly - up to 46 times, depending on the architecture. For instance, top-tier models may use as much as 11.49 kWh to generate 1,000 images, while more efficient systems consume far less. On average, creating 1,000 images accounts for about 10% of a typical U.S. household's daily electricity use.

Strategies to Reduce AI Image Generation's Environmental Impact

Energy Efficiency Improvements

Reducing energy use is a key step toward addressing the environmental challenges posed by AI image generation. For example, models like U-Net are known to consume significantly less energy compared to Transformer-based architectures.

Google demonstrated the potential of energy optimization in May 2025 by achieving a 33x reduction in energy consumption for Gemini Apps prompts. This was accomplished through a combination of techniques, including speculative decoding (where a smaller "draft" model predicts outputs before verification by a larger model), disaggregated serving (separating prefill and decoding steps), and leveraging the XLA ML compiler. As a result, the median Gemini Apps text prompt required just 0.24 Wh of energy.

Other strategies, such as batch inference, help by processing multiple image requests at once, which boosts hardware efficiency and reduces the energy cost per query . Additionally, generating images at the lowest acceptable resolution can make a significant difference - doubling the image resolution can increase energy use by 1.3x to 4.7x, depending on the model.

Timing energy-intensive tasks to coincide with periods when energy grids are powered by renewables - known as carbon-aware scheduling - is another impactful approach . The geographic location of data centers also plays a major role. Hosting models in cooler regions or areas with cleaner energy grids can dramatically lower carbon emissions. While optimizing energy use is essential, emissions can be further reduced through offset strategies.

Carbon Offset Initiatives

Many companies are now turning to carbon-free energy (CFE) procurement to counterbalance AI-related emissions. Google's efforts illustrate this: in 2023, their location-based emission factor was 366 gCO2e/kWh, but with CFE purchases, this dropped to 135 gCO2e/kWh. By 2024, further CFE procurement brought it down to 94 gCO2e/kWh. Combined with software efficiency improvements, Google achieved a 44x reduction in carbon footprint for the median Gemini Apps text prompt within a year.

Real-time carbon intensity tracking tools, such as Electricity Maps, allow developers to schedule non-urgent AI tasks during periods when renewable energy is most available . Meta has also taken notable steps by operating a data center in Lulea, Sweden, where cooler temperatures and renewable energy help reduce cooling costs and overall carbon emissions.

"Making these models more efficient is the single-most important thing you can do to reduce the environmental costs of AI." – Neil Thompson, Director of the FutureTech Research Project, MIT CSAIL

However, carbon offset strategies must also address embodied carbon - the emissions generated during the construction of data centers and the manufacturing of hardware. This is crucial because about 60% of the rising electricity demand for data centers is expected to be met by fossil fuels, potentially increasing global carbon emissions by 220 million tons.

To ensure sustainable AI, it's necessary to consider both operational and infrastructure-related emissions.

Sustainable AI Development Practices

A sustainable approach to AI begins with hardware lifecycle management, which tackles resource consumption at its core. For instance, manufacturing a single 2 kg computer requires around 800 kg of raw materials. Extending hardware lifespans through methods like Design for Disassembly (DfD) and Design for Recycling (DfR) ensures that components like GPUs can be easily separated and recycled at the end of their life .

Modular infrastructure designs also play a pivotal role. By allowing individual components to be replaced or upgraded instead of discarding entire devices, this approach minimizes waste. Predictive maintenance, powered by AI, can further extend hardware life by identifying potential issues before they result in failure. Additionally, take-back programs help recycle outdated hardware, preventing hazardous materials such as lead and mercury from ending up in landfills. This is especially important given that global e-waste reached 53.6 million metric tons in 2020, with only 17.4% officially recycled.

Another promising strategy is edge computing, which involves running AI models on local devices like smartphones instead of centralized cloud servers. This reduces the need for massive data center infrastructure. When combined with model compression techniques - such as knowledge distillation, pruning, and low-rank factorization - it significantly lowers the computational resources needed for inference .

"We need to make sure the net effect of AI on the planet is positive before we deploy the technology at scale." – Golestan (Sally) Radwan, Chief Digital Officer, United Nations Environment Programme

Transitioning data centers to renewable energy sources like solar or wind further reduces reliance on fossil fuels . With AI and machine learning pipelines projected to account for 2% of global carbon emissions by 2030, adopting these sustainable practices isn't just a good idea - it's essential for responsible AI development.

Conclusion

AI image generation carries a hidden energy cost that’s often overlooked. To put it into perspective, generating just one image consumes the same amount of energy as fully charging a smartphone. Multiply that by 1,000 images, and you’re looking at the energy equivalent of driving 4.1 miles in a gasoline-powered car. With some users generating over 1,500 images every week, the environmental impact adds up quickly. This highlights the pressing need for energy-efficient and transparent AI systems.

The problem is further complicated by a lack of openness. As Nature pointed out, "The full planetary costs of generative AI are closely guarded corporate secrets". This secrecy makes it nearly impossible for researchers, policymakers, and the public to grasp the full environmental consequences. By 2026, data centers are projected to consume 1,050 terawatt-hours of electricity annually, putting them among the largest energy users in the world. Greater accountability and sustainable design are necessary to address this challenge.

There are solutions, though. As discussed earlier, some AI models are up to 46 times more energy-efficient. Organizations can take steps like adopting these efficient models, using carbon-aware scheduling, switching to renewable energy, and designing hardware with modularity to extend its lifespan. On an individual level, users can make smarter choices - such as generating fewer images, opting for lower resolutions, using optimized image prompts to reduce retries, and avoiding unnecessary iterations.

"Bigger is better works for generative AI, but it doesn't work for the environment." – Alex de Vries, Ph.D. candidate, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

The AI industry is at a turning point. Since 2020, the rapid growth of data centers has outpaced efficiency improvements, making immediate action critical. Emphasizing transparency, energy efficiency, and responsible development isn’t just about protecting the environment - it’s about ensuring the future of AI itself. By adopting sustainable practices, we can enjoy the creative possibilities of AI while significantly reducing its impact on our planet.

FAQs

How can I estimate the footprint of one AI image I generate?

To gauge the energy impact of creating an AI-generated image, several factors come into play: the type of model, the resolution of the image, and the complexity of the prompt. For instance, generating higher-resolution images can demand up to 4.7 times more energy compared to lower resolutions. Among models, U-Net models tend to be more energy-efficient than their Transformer-based counterparts. To better understand the environmental impact, it's helpful to review the specific model's energy usage data. Additionally, employing techniques like quantization, when supported, can further optimize energy consumption.

Which settings reduce energy use the most (resolution, steps, iterations)?

Reducing the resolution of an image and cutting down the number of steps or iterations during its generation can greatly lower energy use. For instance, increasing the resolution by twofold can lead to energy consumption rising by as much as 4.7 times, while opting for fewer steps directly reduces the energy required.

Is running image generation locally greener than using the cloud?

Running AI image generation on your own hardware can reduce environmental impact, but the outcome hinges on several factors, such as how efficient your hardware is, the energy sources powering it, and how well the model is optimized. Cloud data centers, while powerful, consume massive amounts of energy and contribute to electronic waste. On the other hand, generating images locally avoids relying on cloud infrastructure, but it still requires energy-efficient devices and access to renewable energy to make a real difference. In the end, the environmental footprint of both approaches varies, making it crucial to focus on energy optimization for a more sustainable solution.